From George Street to Manhattan: The remarkable story of Hull’s Jacobs brothers

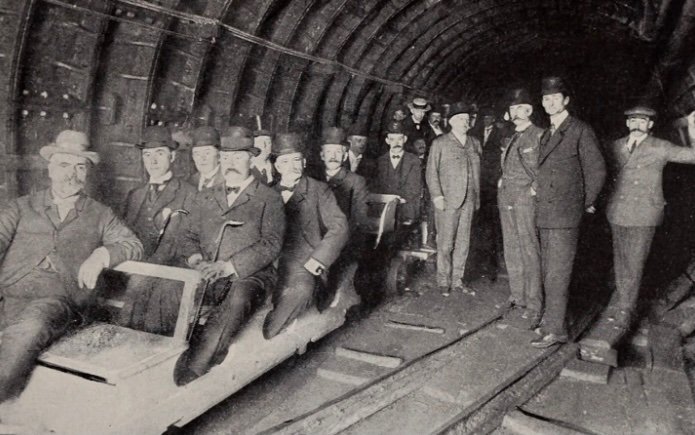

PIONEER: Charles Jacobs, standing on left

Now & Then, a column by Angus Young

The Jacobs brothers

One designed some of the city’s finest landmarks while the other built New York’s first underwater transportation tunnel to bring people to Manhattan from New Jersey.

Today the remarkable story of the Jacobs brothers from Hull has been largely forgotten but, more than a century later, their respective achievements have stood the test of time.

Benjamin Septimus Jacobs and Charles Mattathias Jacobs undoubtedly inherited some of their talents from their father Bethel, one of Hull’s leading figures in the mid-19th century. An inventor, musician, actor and politician, he followed his own father’s footsteps by becoming a silversmith and clockmaker and eventually took over the management of the family jewellers’ shop at 7 Whitefriargate.

LANDMARK: The former Yorkshire Penny Bank overlooking Queen Victoria Square

Bethel Jacobs’ passion for intricate design and emerging technology led him to install an electric time ball outside his shop in 1863, the first device of its kind ever seen in Hull and a forerunner to the timepiece currently being restored on the roof of the Guildhall.

By then, he was one of town’s best-known personalities, having led the promotion of Hull’s industry and commerce at the Great Exhibition in London and playing a leading role in organising the visit of Queen Victoria in 1854. He was made jeweller and silversmith to the Queen in the same year.

Bethel was also a driving force behind several organisations, serving as president of both the Hull Literary and Philosophical Society and the Mechanics’ Institute and being a founder of the Hull School of Art. An active member of the Jewish community, he was also a synagogue president and served as Hull’s Governor of the Poor, initiating the first formal education system for working-class children.

LEGACY: Charles Jacobs, whose rail tunnel under the Hudson River was hailed by the New York Times as ‘one of the greatest engineering feats ever accomplished’

Somehow, amid all this, Bethel and his wife Esther found time to raise 14 children, living for most of their married life in George Street. Brought up in such a household, it’s no surprise that Benjamin and Charles would go on to achieve so much in later life.

Benjamin was just 18 when his father died in 1869 but the prospect of inheriting the family business was not for him. Instead, he trained to become an architect and eventually set up his own practice in Hull.

His best-known surviving work is probably the former Yorkshire Penny Bank overlooking Queen Victoria Square with Caffe Nero now occupying the ground floor. Designed in 1898 to sit on an acutely-angled corner plot, the elaborate Renaissance Revival architectural style not only reflects the bank’s wealth at the time but also Jacobs’ technical flair.

DISTINCTIVE STYLE: The Benjamin Jacobs-designed Western Synagogue in Linnaeus Street

His signature use of brick and terracotta is also in evidence in High Street where he was commissioned to design both the Pacific Exchange and Phoenix Chambers, the former an intended trading centre for grain and oilseed merchants and the latter an office complex standing at the junction of Chapel Lane. Both remain in use today, the Pacific having variously been a private members’ club, the headquarters of the former Humberside Police Authority and the base for the 2017 UK City of Culture team.

Another of his commercial designs is Castle Buildings, currently swathed in scaffolding awaiting refurbishment once improvement works to the adjacent A63 are finally completed. Its location in Castle Street is a nod to its original use as a shipping office, having once stood next to the city’s docks.

Elsewhere, the imposing Wheeler Street Primary School is another Jacobs building, while a deserved city council blue plaque marks his design of the Western Synagogue and adjacent school in Linnaeus Street, which opened in 1902 and where he remained as president until 1926 when he was made a life president. Eventually closed in 1994, the building is now used as an education centre by the city’s Turkish community.

All are now designated as Grade II-listed buildings by Historic England and, collectively, form a significant body of his work over an intensively productive four-year period either side of the dawn of the 20th century. Around the same time, his younger brother Charles was about to embark on the defining project of his own career.

Charles had ambitions to become an engineer and, after completing a five-year apprenticeship at Earles shipyard in Hull, he travelled to China to work on bridge building schemes for the firm before going to sea for three years to qualify as a marine engineer. He also became a surveyor for the shipping insurance firm Lloyds.

He eventually set himself up as a consultant engineer, initially in Cardiff where he oversaw the construction of a dry dock and later applied his skills to various engineering roles in the nearby South Wales coalfields. The latter would lead to an invitation to visit the coalfields of Philadelphia and by 1891 he had opened an office in New York.

A year later he was hired by the East River Gas Company to build a tunnel connecting the firm’s factory on Long Island to Manhattan. His successful design carried gas pipes. His next tunnel would carry electric trains.

Two previous attempts to build a rail tunnel under the Hudson River had failed, with 20 men dying in a fatal explosion during one of them. However, Charles came up with a construction method that not only worked but has stood the test of time. It still carries trains to this day.

GIVING BACK: The site of the original Jacobs Homes almshouses near Pickering Park

He solved two major problems during the build. Solid rock which had previously proved impenetrable was blasted for 11 months to form the route while he successfully solved the mystery surrounding slight but regular movements detected in completed sections of the tunnel by concluding they were being caused by the river’s tides. The project’s investors were nervous but he judged the risk of damage or even collapse was minimal. He was proved right.

When it opened in 1906, Charles Jacobs’ tunnel was hailed by the New York Times as “one of the greatest engineering feats ever accomplished, perhaps even greater than the Panama Canal”. He would build six more tunnels bringing trains and their commuters into Penn Station, effectively paving the way for the development of Midtown Manhattan.

He later built tunnels under the Seine in Paris and was in charge of huge engineering projects in places such as Mexico, Canada, Russia and India. He died in 1919, aged 69, but his name still lives on in a quiet corner of Hull.

The Charles M. Jacobs charity was established after his death to build a small estate of almshouses near Pickering Park, intended for the over-60s with a preference given to members of the city’s Jewish community. The original properties were replaced with new ones in 2013 by Pickering and Ferens Homes but the street name – The Jacobs Homes – remains.

Become a Patron of The Hull Story. For just £2.50 a month you can help support this independent journalism project dedicated to Hull. Find out more here