The birth of aviation in the city

‘GRACEFUL CURVES’: The Ling-Newington monoplane, May 1910

The Way it Was

In partnership with Hull History Centre

By Kyle Thomason, archivist/librarian

The history of aviation in Hull starts with Thomas Walker, a painter who published his work on mechanical flight, A Treatise Upon the Art of Flying, in 1810. It was one of the earliest books of its kind.

The aircraft he designed was an ornithopter in design – an aircraft that flies through flapping wings, imitating a bird.

Almost a century later, aviation was still in its infancy but Edward Ling was designing his very own aircraft in his workshop – the Ling Monoplane.

The first mention of the aircraft relates to an aviation event at the Marine Gardens, Portobello, Edinburgh. The directors offered a £500 prize for the first flight across the Firth of Forth.

Ling, was born in Hull in July 1886 to Miles and Elizabeth Ling. In his teens he became interested in aeroplane model making, and he soon became apprenticed as a mechanical engineer.

It is not clear when Ling started his full-scale construction as he kept it a secret, but he had ‘…given the science of aviation much study’ (Hull Daily Mail, September 28, 1909).

When a representative from the newspaper visited his workshop on Walton Street, he described the aircraft as follows: ‘The structure was shaped very much like a canoe, with graceful curves. The bent wood ribs are of very light design… The Planes [wings] have been constructed on a light frame covered with aero cloth… The width where these planes are spread out is 32ft, and they can be so tilted that should the engine suddenly stop the aviator can “plane” or glide safely… the tail, light but of great strength, ready also to be fixed. At the end is to be fitted the rudder, of thin but unbendable maple, which will work on brass hinges. Weight has, of course, been avoided, a matter of ounces being considered serious… The machine is the result of no hastily-thought out plans.’ (Hull Daily Mail, September 28, 1909).

‘The propellor is of aluminium and alloy (a Hull discovery) – so that it will bend without breaking… Aluminium has been used greatly in the construction. The planes, for example, are fitted into aluminium boxes. Mr Ling’s seat in the canoe-shaped central body, strengthened with light steel ribs, is water-tight to enable it to float.’ (Hull Daily Mail, October 28, 1909).

At the time of the visit, Ling had left for Edinburgh to finalise the arrangements for his upcoming flight. It was to be around nine miles across the Forth landing near Burtisland.

It was reported that he had already carried out a flight of four miles in his machine, and in an interview with The Scotsman in October he stated that he had conducted various experimental flights in the neighbourhood of Hull in strict secrecy, often at daybreak.

His planned flight was reported across the country, and he had intended to carry out a public trial flight in Hull so the people of the city could view the machine.

However, his aircraft was still being adjusted and propped for the Forth flight and trouble with the ignition of the engine delayed his trip.

His planned attempt would be on October 23, 1909 but the flight was postponed until the following Saturday, due to more engine issues.

The engine in question was of his own idea and built by another Hull local, Thomas Leonard Bell, of St George’s Road, an engineer with the British Steam Trawling Company.

It was a three-cylinder engine, that though light, could produce 40 horsepower, easily enough to power the aircraft.

On October 28, he left Hull along with his aircraft. He was described as: ‘A smart-looking young man… dressed in a neat blue suit, his lack of words and general demeanour gave a mail representative the impression that here was a man who had determination to carry a difficult thing through.’ (Hull Daily Mail, October 28, 1909)

He arrived at Waverley Station in the early afternoon, by which time his aircraft had been loaded onto a lorry and transferred to the Marine Gardens.

The total cost of the aircraft up to this point was about £700, which was more than the winning prize.

While on show at the gardens it was noted as being: ‘…a marvel of ingenuity and delicate workmanship and embodies many novelties and patents.’ (The Scotsman, October 29, 1909)

Ling decided to patent much of his work on the aircraft and the engine as it was wholly designed by him and there was much interest and many requests to inspect it including, it was reported, two German agents.

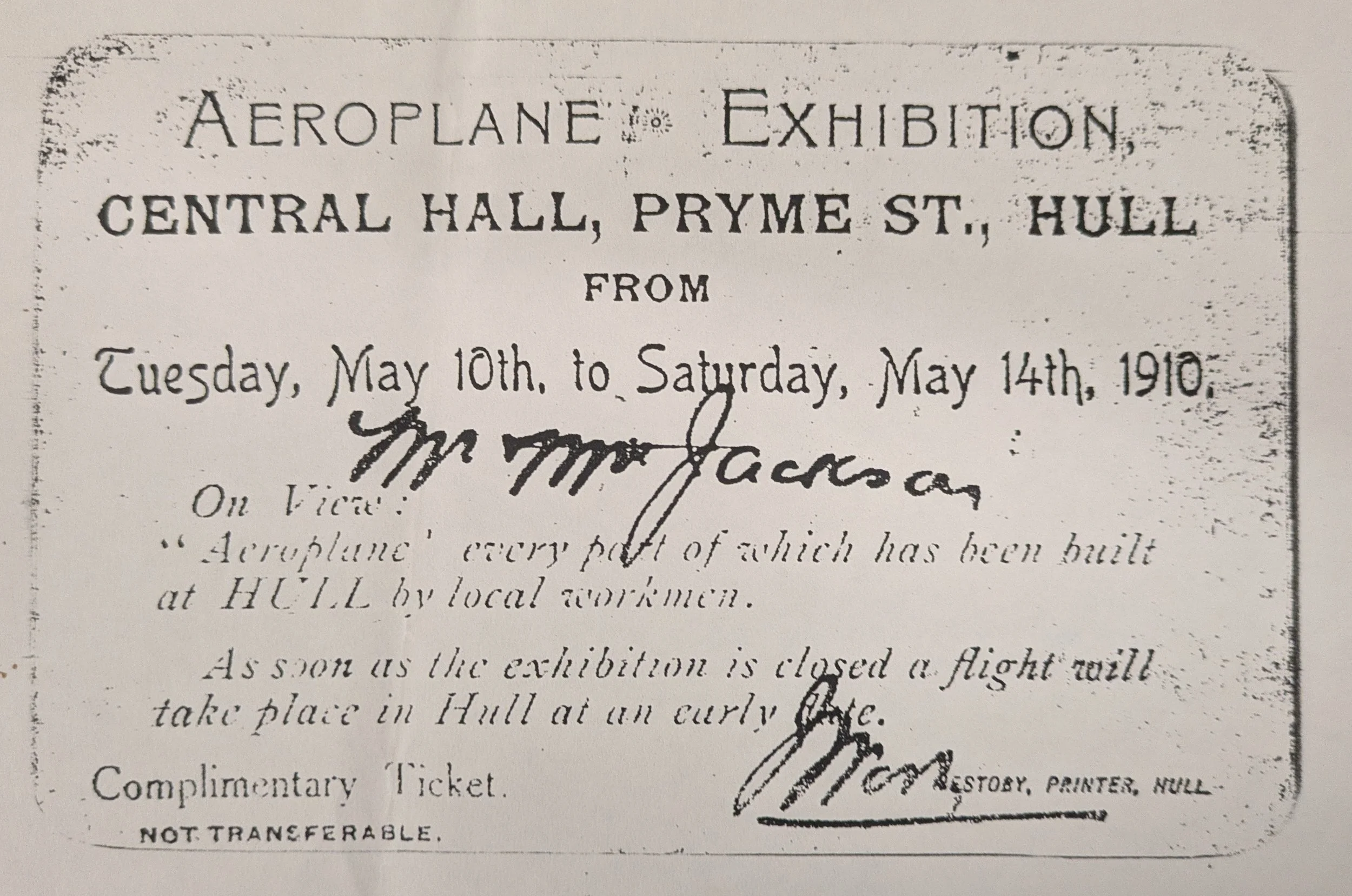

TICKET TO FLY: An exhibition invitation to the Hull-made aeroplane

The engine troubles were in the past as it had run in Hull for several hours straight in a trial.

Unfortunately, Ling had to delay the flight once again.

Despite the mechanics working through the night, the engine had been slightly damaged in transit and the carburettor left back in Hull.

Great disappointment was had amongst the public but after another week the finishing touches were put to the aircraft, and it was ready for its first trial outing on November 8.

The aircraft was brought out to the promenade and an attempt made to start the engine, however, a crack in the propellor socket and defect in one of the blades was spotted crucially before the engine fully turned over.

A fresh wooden propellor was sent for and the aircraft once again dismantled.

Despite all this, Ling remained optimistic and declared that he would not return to Hull without giving it a try. On November 20, 1909, it was reported in the Hull Daily Mail that Ling: ‘… had a successful [test] flight of two miles and a quarter, and was quite satisfied with the behaviour of his monoplane…’

Unfortunately, there is no other mention of the flight and the following week he returned to Hull with his aircraft with the intention of trying again later.

Between the end of November and May the following year nothing more is heard of either Ling or his monoplane.

It appears that Bell and his brother William took over the lead on the monoplane which was now owned by the Newington Monoplane Company, a syndicate of Hull businessmen.

Bell, it seems, altered the design slightly. It now had shorter wings and weighed an extra 100lbs with additional engine alterations.

On May 10, the aircraft was exhibited at Central Hall, Pryme Street, for a few days whereupon the public could come and view it for a fee. Both the Hull Aero Club and Hull & East Riding Aero Clubs were in attendance.

One month later and the aircraft was taken to land owned by George Vickerman at Sunk Island for trials.

It was brought out and run briefly before the wheels were seriously damaged due to the state of the ground, which had been grazed by horses all winter.

The aircraft remained onsite at Sunk Island in preparation for further trials. However, on June 29, 1910, there was a ghastly thunderstorm, and their tent was blown away along with much of the companies supplies.

The aircraft was then struck by lightning and described as: ‘… a complete wreck. The body of the machine was cut in two and the wheels and planes severed.’ (Hull Daily Mail, July 30, 1909)

The machine was brought back to Hull a few days later at which time one of the men involved stated that: “We have had very bad luck all the way through – the devil seems to have been in the thing.”

This was made even more upsetting when the aircraft was set for a flight just a few days later.

The machine was salvaged and rebuilt in some capacity and taken this time to Hedon Racecourse, where Oscar S. Penn – a would-be pilot from Hull – smashed the aircraft to pieces in attempting to fly it.

Thus ended the story of the Ling/Newington monoplane. At least, the first version of it!