Jacob Bronowski: How MI5 failed to thwart an intellectual genius

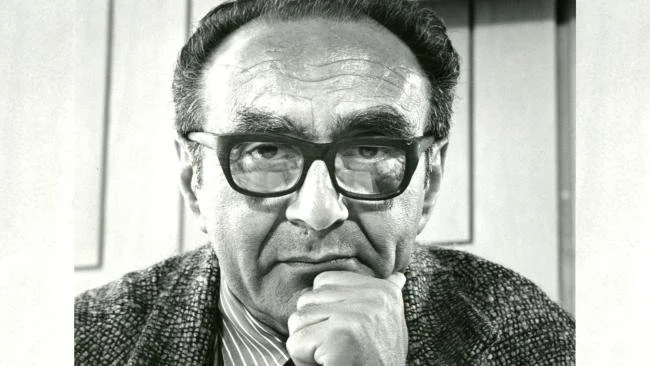

JACOB BRONOWSKI: Scientist, communicator, humanist, poet, documentary maker, chess player

Now & Then, a column by Angus Young

The remarkable life of Jacob Bronowski

A simple blue plaque on a house in Hallgate is easily missed if you happen to be heading into the centre of Cottingham.

It commemorates a man who was arguably one of the important figures of 20th-century Britain.

Scientist, philosopher and broadcaster Jacob Bronowski lived there after moving to Hull in 1934 to teach mathematics at the city’s new University College, later to become Hull University.

A brilliant academic, he eventually became best known as the presenter and author of The Ascent of Man, a 13-part BBC TV documentary screened in 1973 charting the development of human society through its understanding of science. It’s still widely regarded as a landmark piece of television history.

However, his career could have ended in ignominy in Hull where, unknown to him, he was put under surveillance by MI5 who suspected he was a national security risk.

Born to a Polish-Jewish family, he moved to Britain from Germany in 1920 as a 12-year-old after his parents fled the Russian occupation of his native Poland.

INTRIGUE: The former Haworth Arms in Beverley Road where an undercover police officer snooped on Jacob Bronowski

Despite knowing only two words of English on arrival, he went on to study mathematics at Cambridge University before securing a teaching job in Hull a year after becoming a British citizen.

In 1939 a letter was sent to the Home Office from an anonymous teacher whose son had met Bronowski in Hull. It was claimed he was “reviling this country” and “extremely left”. The implication was that he was an active Communist.

Inquiries were made with the police in Hull who were asked if he was known to them. They replied he wasn’t a member of any Communist organisation and, as far as they were aware, was pro-British.

Despite this, the academic rumour mill refused to die down. A year later the secret service received another tip, this time from an eminent linguist, Professor William Collinson at Liverpool University, who personally knew an officer at MI5.

Collinson quoted anonymous colleagues of Bronowski in Hull who considered him “an agitator of the Communist type” who was “disseminating seditious doctrines”.

Once again, the police in Hull were asked to investigate and an almost comical cloak-and-dagger surveillance was launched into the still unsuspecting university teacher.

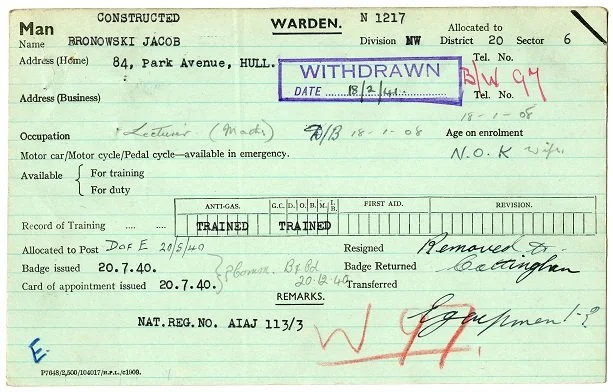

HOME FRONT: MI5 thought Bronowski was a security risk. In fact he volunteered as an air raid warden in Hull. Picture credit: Hull History Centre

MI5 files released four decades after his death not only revealed the two tip-offs but also fascinating details of the undercover police operation carried out at MI5’s request.

While Bronowski’s home was watched, a PC Alfred Foster was sent to various public events to observe him at a discreet distance.

At a meeting of the Left Book Club in the Haworth Arms in Beverley Road, Foster noted that Bronowski not only chaired proceedings but was also overheard saying he was willing to “collaborate” with Communists on certain issues he was sympathetic with.

Three months later Foster was still on his trail, this time at a meeting of the People’s Theatre Guild.

In his report, the officer recorded that a series of comedy sketches performed during the evening were critical of the ruling classes and the British Empire while Bronowski had taken to the stage to read a self–written poem apparently titled How I Hate War.

However, Foster acknowledged having difficulty hearing all the words and admitted the poem seemed “extremely pacifist”. Even so, he concluded his quarry was “Communist in all but name”.

RESIDENCE: 84 Park Avenue, where Bronowski lived in Hull

In reality, Bronowski was not a member of the Communist Party or the Young Communist League; he did not attend any of their meetings and no further incriminating evidence against him was unearthed.

As for his poetry, it’s probable that PC Foster was completely unaware he had co-edited a literary magazine while at Cambridge and had subsequently published his first book – not on mathematics but on poetry.

Long after his death, Bronowski’s daughter Professor Lisa Jardine would not only discover the secret MI5 files on her father in the National Archives but also evidence of his active participation in the war effort in Hull.

Far from being anti-British, he had served as a volunteer air raid warden in his adopted home city while living in Park Avenue. His Air Raid Precautions personnel card is now part of the archive collections at the Hull History Centre.

Despite this, PC Foster’s report formed the basis of MI5’s view on Bronowski for many years. As far as the spooks were concerned, he remained a security risk until the 1950s.

In 1943, with plans being drawn up to start the mass bombing of German cities, the Ministry of Home Security started looking for an expert mathematician to help them calculate and model the likely impact of the raids.

SUBURBIA: The house in Hallgate marked with a blue plaque where Bronowski lived in Cottingham

Asked for a view on Bronowski, MI5 gave a negative report but the Ministry appointed him anyway as he was the best qualified person.

The decision infuriated senior officials at MI5 who warned that anything secret seen by him would go “straight to Communist Party headquarters”.

Instead, he kept his secret work to himself and actually avoided discussing much of it for the rest of his life. Many believe the horrific death toll during the bombings haunted him.

Even so, his work was so effective that he was invited to the United States to advise them on their attacks on Japanese cities.

After the two atomic bombs were dropped, he was part of a British team of scientists and engineers who visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki to study the aftermath and its implications for future UK civil defence.

TRIBUTE: The plaque honouring Bronowski in Hallgate

A year later he spoke to the BBC about what he had seen and his powerful testimony launched his broadcasting career.

In the Ascent of Man, Bronowski visited the Auschwitz concentration camp where many members of his Polish family had died during the Second World War.

In a memorably bleak scene, he walks through pools of muddy water where his relatives’ ashes were dumped and delivers one of the all-time great monologues to the camera.

“It is said that science will dehumanise people and turn them into numbers,” he says.

“This is the concentration camp and crematorium at Auschwitz. This is where people were turned into numbers.

“Into this pond were flushed the ashes of four million people. And that was not done by gas. It was done by arrogance. It was done by dogma. It was done by ignorance. When people believe they have an absolute knowledge, with no test in reality – this is how they behave. This is what men do when they aspire to the knowledge of gods.”

As a kid, I remember watching the scene in silent awe. It’s still available online and I would highly recommend giving it a watch.

Scientist, communicator, humanist, poet and chess player (he was Hull chess champion in 1935 and Yorkshire champion in the following year), Dr Jacob Bronowski died in 1974.

His biographer Timothy Sandefur summed him up perfectly.

“He was involved in nearly every major intellectual undertaking in the 20th century. He was a serious philosopher who was responsible for probably the finest documentary ever made.”