How voyage Down Under changed lives forever

‘TRANSPORTATION BEYOND THE SEAS’: A view of the First Fleet, in Botany Bay

The Way it Was

In partnership with Hull History Centre

By Neil Chadwick, archivist/librarian

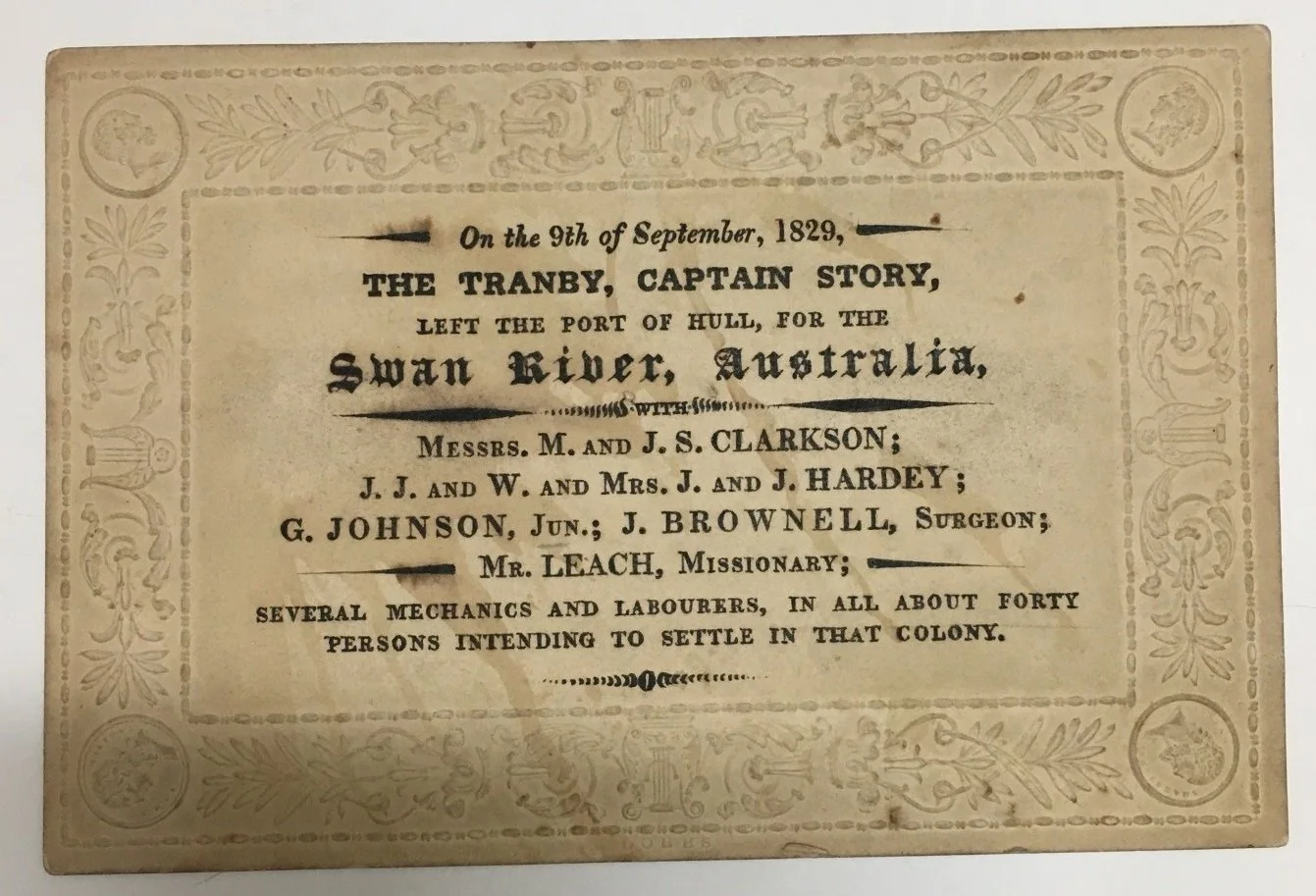

February marks the 196th anniversary since the arrival of the ship, The Tranby, in Western Australia.

The Tranby left Hull in September 1829. Making the journey were men, women, children, animals, together with all their worldly belongings.

Those onboard settled on the Swan River, what is now modern-day Perth.

These were not the first people from this area to travel to Australia. In 1787, the First Fleet left Britain. Its aim was to establish the first permanent colony in Australia.

Amongst those aboard were three criminals who had committed offences in Hull. This is the story of their journey and their lives, and others who settled for a new life in Australia.

Two-and-a-half years earlier, on October 7, 1784, William Dring, possibly of Hedon, no more than 14-years-old, pleaded guilty to petty larceny at the Hull Quarter Sessions. In return, he was ‘sentenced to be transported beyond the seas for seven years’.

Dring was not alone. Also pleading guilty alongside him was Joseph Robinson. He too received seven years transportation.

A third individual also implicated was John Hastings. Hastings, however, denied the charge. Tried by jury, he was later found not guilty.

The offence – or, in the case of Hastings, the alleged offence – took place five weeks earlier on August 24, when it was said Dring, Robinson and Hastings stole and made away with a pair of trousers and several other things which were the goods and chattels of Joseph Mitchinson, including bottles of brandy.

Pleading guilty, Dring and Robinson were moved to the Gaol (prison) which was then at the junction of Market Place and Mytongate. From here, they were to await transportation to Australia.

Attempts were made for Dring to receive a lighter sentence and even a pardon, perhaps owing to his age. A reputed opportunity of employment in return for leniency was also put forward. Despite such attempts, the sentence stood. The shackles remained steadfast.

At the same session, Robert Nettleton was sentenced to seven years transportation for a similar offence, while Mary Atkinson was also sentenced to transportation, but ‘obtained his majesty’s free pardon’, though we are uncertain why this was.

On April 26, 1785, Dring, Robinson and Nettleton were transferred to the prison hulks in the river Thames to await their voyage to Australia.

It would, however, be another two years before all three were sent to serve out their sentences on the other side of the world.

What makes this story unique in Hull’s history is these men were among the 11 ships of the First Fleet which set sail for Australia.

SEALING THEIR FATE: The conviction of William Dring, Joseph Robinson and Robert Nettleton, and the pardon of Mary Atkinson

The First Fleet, under the command of Captain Philips, was to establish a new (and first) British settlement.

Over 1,400 persons set out, making the journey to the other side of the world, before eventually arriving at Botany Bay (now modern-day Sydney) on January 19, 1788. The ship Dring and co sailed on was the Hull built vessel, Alexander.

The voyage to Australia was the first of many challenges.

Hull man George Benson, in his account of transportation in 1840, described the voyage as “fraught with misery”.

The First Fleet, however, did make the voyage largely unscathed. Of the 1,420 persons that left, 1,373 arrived at Botany Bay.

The Second Fleet, however, which left for Australia just under two years later, was notorious for its poor conditions whilst at sea. Many became ill, with a quarter dying before their arrival. Many arrived riddled in lice, while 40 per cent of those that arrived died within the first six months.

Early settlers and convicts had to deal with the harsh conditions of Australia. Those serving transportation sentences, for example, worked from sunrise to sunset. They were not paid.

Punishment was physical. Lashes to the back were common. Some were placed in chains and heavy irons to make their work harder.

Female convicts were punished with hard labour and solitary confinement with just bread and water. Such punishments would have impacted their mental health and wellbeing.

For those who served a seven or fourteen-year transportation sentence, the options were to return home or see out their days in Australia. Of course, for those transported for life, their stay was indefinite.

Benson returned home to Hull after his sentence and published his account of the Horrors of Transportation.

Others chose to remain. Those who left Hull aboard The Tranby in 1828 to settle in what is now Western Australia are all believed to have remained in Australia. For example, father and son, John and Joseph Hardey were influential figures in the early development of the Belmont area of what is modern-day Perth. Tranby House, on the Swan River, was built by John Hardey.

Those who went out to Australia viewed the Aboriginal people with curiosity but also suspicion. And naturally, this was very much reciprocated by the Aboriginal people. It wasn’t long until both sides clashed.

Shortly after the arrival of the First Fleet, conflict with the Cadigal, but also the Bidjigal peoples, broke out, despite official policy of the British government for the colony to establish friendly relations.

There are no accounts of any Hull settlers in direct conflict with Australia’s Aboriginals. Dring, Robinson and Nettleton possibly witnessed, heard, or perhaps participated in these early conflicts.

PETTY CRIMINALS: The order for the transportation of William Dring, John Nettleton and Joseph Robinson

A Hull man who emigrated to Australia via Melbourne recalled how it was not uncommon for miners to carry firearms when travelling from Melbourne to the gold mines for protection (probably also in fear and suspicion of their fellow settlers).

Of those three Hull men who went out with the First Fleet, Dring remained. He was, however, unable to stay out of trouble, and was sent to Norfolk Island.

The reputation of Norfolk Island, set up as an offshoot by some from the First Fleet, was notorious among convicts, particularly those deemed unruly or trouble causers.

Dring was reputed to have started a fire on the vessel Sirus. He is also reputed to have stolen potatoes.

Robinson too fell into trouble. It is said he killed pigeons that were reserved for those most in need. Certainly, taking Benson’s account, one could argue Robinson and Dring, like others, had no option given the conditions and the treatment they endured.

Nettleton and Robinson eventually left, presumably free men after serving their sentences.

Attempted escapes were not uncommon, and in a few cases, some were successful.

A Liverpool man transported for seven years tried on several occasions to escape. He finally made good his escape and returned to England. It was whilst in his hometown of Liverpool that he was picked up, presumably after being recognised.

Despite pleas recounting the horrors (even the judge sympathising and recognising the misery he suffered) the judge had little option than to re-impose the sentence of transportation, but this time for the term of his natural life.

Dring remained in Australia after his sentence expired, or at least for a while. In 1792, he married Ann Forbes. Together, they had a daughter, Elizabeth (born1794) and son Charles (born 1796) and settled in New South Wales.

It is not known what happened to him after this. He may have died by 1798. Another theory is he had left Australia altogether, with one suggestion that he died in 1845 after drowning at sea.

However, we will never really know what happened to William Dring.

With Hull being a port, there is little doubt Australia and opportunities it provided were discussed in the town. It wasn’t uncommon for ships to sail direct from Hull to Australia.

One Hull ship, under its Hull master, was implicated in what the Adelaide Observer described as ‘disgraceful proceedings whilst enroute to Australia’. It was reported the vessel was a ‘floating brothel full of evil sea-monsters’. Neglect of duty was also reported against the ship’s surgeon for not attending to those unwell.

The voyage to Australia continued to be dangerous. Hull man Francis Brown recalled in a letter home that despite the outward voyage taking 112 days (less than half the time of the First Fleet) he arrived in good health, though a number of the ship’s passengers and crew weren’t so lucky due to cholera having spread throughout the ship.

TICKET TO RIDE: Immigration card of The Tranby

When the settlers arrived, they had to contend with the heat, which was too hot to be pleasant.

A Hull man living in Townsville wrote home to his former employer saying the heat was no cooler than a warm summers day in England. Insects plagued many people’s thoughts when writing back home, often describing sleep as impossible.

The cost of living in Australia was expensive. In Melbourne, for example, a Hull man who emigrated in the mid-19th century reported home that everything was expensive and whatever money was had, ‘evaporated quickly’.

Arriving in Melbourne, Francis Brown recalled how necessities were cheap, yet items such as clothing were much dearer than back in England.

Many people were ill equipped for Australia’s climate. The Hull Packet reported many being caught out with inadequate clothing, and that specialist retailers were available in Hull offering appropriate clothing for Australia’s climate.

And of course, nothing could prepare those being away from their family and friends. A young woman, named Mary, who left Hull for Australia, wrote home to her father saying how she missed him, home and her friends.

The influx of settlers led to surplus labour force. Permanent employment was difficult to find. A Hull man in Adelaide reported that due to the abundance of men arriving, many walked the streets of Adelaide looking for employment. The Hull man in Townsville reported ‘the abundance of workers drove down wages, and that jobs were temporary, usually lasting just a few weeks at a time’.

Many young men saw their opportunities in the emerging gold mines of Australia. However, for many, the promise of riches simply did not materialise.

One Hull man who tried his hand in the gold mines north of Melbourne described men abandoning the mines to seek out opportunities elsewhere, thus only adding to the oversupply of labour.

Despite challenges and hardships, many remained, forging out a life for themselves and their families.

The experience of people from Hull transported to Australia highlights the harsh realities of colonial life.

It serves as a reminder of the human cost of British expansion and the impact of transportation on individuals and communities, but also their contribution in the settling of modern Australia.